From the award-winning author of The Unwinding–the brilliantly told saga of the ambition, idealism, and hubris of one of the most legendary and complicated figures in recent American history, set amid the rise and fall of U.S. power from Vietnam to Afghanistan. Richard Holbrooke was brilliant, utterly self-absorbed, and possessed of almost inhuman energy and appetites. Admired and detested, he was the force behind the Dayton Accords that ended the Balkan wars, America’s greatest diplomatic achievement in the post Cold War era. His power lay in an utter belief in himself and his idea of a muscular, generous foreign policy. From his days as a young adviser in Vietnam to his last efforts to end the war in Afghanistan, Holbrooke embodied the postwar American impulse to take the lead on the global stage. But his sharp elbows and tireless self-promotion ensured that he never rose to the highest levels in government that he so desperately coveted. His story is thus the story of America during its era of supremacy: its strength, drive, and sense of possibility, as well as its penchant for overreach and heedless self-confidence. In TK, drawn from Holbrooke’s diaries and papers, we are given a nonfiction narrative that is both intimate and epic in its revelatory portrait of this extraordinary and deeply flawed man, and the elite spheres of society and government he inhabited”–Publisher’s description

From the award-winning author of The Unwinding–the brilliantly told saga of the ambition, idealism, and hubris of one of the most legendary and complicated figures in recent American history, set amid the rise and fall of U.S. power from Vietnam to Afghanistan. Richard Holbrooke was brilliant, utterly self-absorbed, and possessed of almost inhuman energy and appetites. Admired and detested, he was the force behind the Dayton Accords that ended the Balkan wars, America’s greatest diplomatic achievement in the post Cold War era. His power lay in an utter belief in himself and his idea of a muscular, generous foreign policy. From his days as a young adviser in Vietnam to his last efforts to end the war in Afghanistan, Holbrooke embodied the postwar American impulse to take the lead on the global stage. But his sharp elbows and tireless self-promotion ensured that he never rose to the highest levels in government that he so desperately coveted. His story is thus the story of America during its era of supremacy: its strength, drive, and sense of possibility, as well as its penchant for overreach and heedless self-confidence. In TK, drawn from Holbrooke’s diaries and papers, we are given a nonfiction narrative that is both intimate and epic in its revelatory portrait of this extraordinary and deeply flawed man, and the elite spheres of society and government he inhabited”–Publisher’s description

Category: Books (Page 6 of 10)

KIRKUS REVIEW

KIRKUS REVIEW

A novelistic tech tale that puts readers on the front lines of cybersecurity.

For all whose lives and connections depend on the internet—nearly everyone—this biography of the pseudonymous “Alien” provides a fast-paced cautionary tale. Smith (Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients., 2015, etc.) has enough experience as a computer programmer to understand the technicalities of this world, but his storytelling makes it intelligible to general readers; indeed, the narrative is more character-driven than technology-driven. The book requires a few leaps of faith—not only that Alien is who the author says she is, but that she can so vividly recount events and conversations that happened years before she met the author. The story begins with Alien at MIT. Lacking focus and direction, she was drawn to a hacking community in a time when the term could extend from picking locks to taking drugs and didn’t become more focused on technology until computers became more central to society. The hackers often lived more adventurous lives than many students, and Alien experienced plenty of casual sex, drug use, and a few tragic casualties along the way. She graduated from hacking computer systems to helping protect them from hackers at a time when “Corporations from Microsoft and Cisco on down had begun hiring hackers of their own to help defend themselves against other hackers.” Some worked one side of the fence, some worked the other, and some straddled the line and were capable of “going rogue.” Smith goes into great detail to demonstrate how Alien could penetrate the security of whomever was employing her, showing how a real criminal would do it, and makes fearfully clear that there is “no such thing as absolute security in this world, or any definitive and final fixes.” Alien now runs a small hacking company that assists with security for banks, governments, and other organizations.

A page-turning real-life thriller, the sort of book that may leave readers feeling both invigorated and vulnerable.

KIRKUS REVIEW

KIRKUS REVIEW

How one Frenchwoman’s spy network helped win the war against the Nazis.

Marie-Madeleine Fourcade (1909-1989) was raised in a well-to-do French family, but she was extremely independent for her time and refused to comply with the unstated rules of proper feminine behavior. “All her life,” writes Olson (Last Hope Island: Britain, Occupied Europe, and the Brotherhood That Helped Turn the Tide of War, 2017, etc.), “she rebelled against the norms of France’s deeply conservative, patriarchal society.” When she was approached to work with an espionage group to help the Allies before the onset of World War II, she accepted the position with little hesitation. Following this life-changing decision, she became the eventual leader of the group known as “Alliance,” a vast network of spies and radio operators who worked all over France. In a comprehensive, often exciting narrative, the author chronicles the actions of Fourcade and Alliance from 1936 to 1945. Her use of quotes and solid descriptive passages help re-create the tension and anxiety Fourcade and her friends felt as they risked everything to save France. Olson also effectively integrates a thorough history of the role of the Vichy government during this time as well as details on how MI6 and the Allies used the information Alliance collected to change the course of the war. She shares specifics on many of the agents under Fourcade’s control, their daring exploits and escapes, and what happened to those captured by the Germans. With the same attention to detail, Olson writes about Fourcade’s secret lover and her children. Although the text is overlong, the author brings into the spotlight a woman whose courage and endurance helped shape history yet whose full story had not yet been told. “For several decades following the war,” writes the author, “histories of the French resistance, which were written almost exclusively by men, largely ignored the contributions of women.” Olson rectifies that omission.

An engaging, informative addition to World War II history.

Meticulously reported, exquisitely written, and grippingly told, Say Nothing is a work of revelation.” –David Grann, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Killers of the Flower Moon From award-winning New Yorker staff writer Patrick Radden Keefe, a stunning, intricate narrative about a notorious killing in Northern Ireland and its devastating repercussions In December 1972, Jean McConville, a thirty-eight-year-old mother of ten, was dragged from her Belfast home by masked intruders, her children clinging to her legs. They never saw her again. Her abduction was one of the most notorious episodes of the vicious conflict known as The Troubles. Everyone in the neighborhood knew the I.R.A. was responsible. But in a climate of fear and paranoia, no one would speak of it. In 2003, five years after an accord brought an uneasy peace to Northern Ireland, a set of human bones was discovered on a beach. McConville’s children knew it was their mother when they were told a blue safety pin was attached to the dress–with so many kids, McConville always kept it handy for diapers or ripped clothes. Patrick Radden Keefe’s mesmerizing book on the bitter conflict in Northern Ireland and its aftermath uses the McConville case as a starting point for the tale of a society wracked by a violent guerrilla war, a war whose consequences have never been reckoned with. The brutal violence seared not only people like the McConville children, but also I.R.A. members embittered by a peace that fell far short of the goal of a united Ireland, and left them wondering whether the killings they committed were not justified acts of war, but simple murders. From radical and impetuous I.R.A. terrorists–or volunteers, depending on which side one was on–such as Dolours Price, who, when she was barely out of her teens, was already planting bombs in London and targeting informers for execution, to the ferocious I.R.A. mastermind known as The Dark, to the spy games and dirty schemes of the British Army, to Gerry Adams, who negotiated the peace and denied his I.R.A. past, betraying his hardcore comrades–Say Nothing conjures a world of passion, betrayal, vengeance, and anguish

Meticulously reported, exquisitely written, and grippingly told, Say Nothing is a work of revelation.” –David Grann, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Killers of the Flower Moon From award-winning New Yorker staff writer Patrick Radden Keefe, a stunning, intricate narrative about a notorious killing in Northern Ireland and its devastating repercussions In December 1972, Jean McConville, a thirty-eight-year-old mother of ten, was dragged from her Belfast home by masked intruders, her children clinging to her legs. They never saw her again. Her abduction was one of the most notorious episodes of the vicious conflict known as The Troubles. Everyone in the neighborhood knew the I.R.A. was responsible. But in a climate of fear and paranoia, no one would speak of it. In 2003, five years after an accord brought an uneasy peace to Northern Ireland, a set of human bones was discovered on a beach. McConville’s children knew it was their mother when they were told a blue safety pin was attached to the dress–with so many kids, McConville always kept it handy for diapers or ripped clothes. Patrick Radden Keefe’s mesmerizing book on the bitter conflict in Northern Ireland and its aftermath uses the McConville case as a starting point for the tale of a society wracked by a violent guerrilla war, a war whose consequences have never been reckoned with. The brutal violence seared not only people like the McConville children, but also I.R.A. members embittered by a peace that fell far short of the goal of a united Ireland, and left them wondering whether the killings they committed were not justified acts of war, but simple murders. From radical and impetuous I.R.A. terrorists–or volunteers, depending on which side one was on–such as Dolours Price, who, when she was barely out of her teens, was already planting bombs in London and targeting informers for execution, to the ferocious I.R.A. mastermind known as The Dark, to the spy games and dirty schemes of the British Army, to Gerry Adams, who negotiated the peace and denied his I.R.A. past, betraying his hardcore comrades–Say Nothing conjures a world of passion, betrayal, vengeance, and anguish

Tom igoe has written an excellent critique and background piece:

https://dariendma.org/wp-content/uploads/Notes-on-Say-Nothing.pdf

Victor Frankenstein, son of an illustrious Swiss family seems to have everything: wealth, youth, friends and family. He also has a burning desire for knowledge which he aims to satiate by studying at the prestigious Ingolstadt University. However his passion for learning leads him to perform a deed as terrible as it is marvelous. He finds the secret to life itself and builds a man, a towering monster of a man and endows it with life. Horrified and repulsed by his own creation, Frankenstein flies from the university and from anything related to his field of research. Shocked and weakened by his labors and the horror he has endured, Frankenstein becomes an unhappy shadow of his former self. He returns home to find that his creation is sentient, aware of him and has already committed murder. Shunned by all, lonely and abandoned by even its creator, the miserable monster requests him to make a companion for him. Frankenstein refuses to unleash another such fiend upon the human race. A struggle begins between the two: the maker and his fiend- A struggle that can end only in complete destruction of either- A struggle that will reveal the true nature of both. It raises the question: who is the true author of evil, the creator or the creation?

Victor Frankenstein, son of an illustrious Swiss family seems to have everything: wealth, youth, friends and family. He also has a burning desire for knowledge which he aims to satiate by studying at the prestigious Ingolstadt University. However his passion for learning leads him to perform a deed as terrible as it is marvelous. He finds the secret to life itself and builds a man, a towering monster of a man and endows it with life. Horrified and repulsed by his own creation, Frankenstein flies from the university and from anything related to his field of research. Shocked and weakened by his labors and the horror he has endured, Frankenstein becomes an unhappy shadow of his former self. He returns home to find that his creation is sentient, aware of him and has already committed murder. Shunned by all, lonely and abandoned by even its creator, the miserable monster requests him to make a companion for him. Frankenstein refuses to unleash another such fiend upon the human race. A struggle begins between the two: the maker and his fiend- A struggle that can end only in complete destruction of either- A struggle that will reveal the true nature of both. It raises the question: who is the true author of evil, the creator or the creation?

From the great historian of the American Revolution, New York Times-bestselling and Pulitzer-winning Gordon Wood, comes a majestic dual biography of two of America’s most enduringly fascinating figures, whose partnership helped birth a nation, and whose subsequent falling out did much to fix its course.Thomas Jefferson and John Adams could scarcely have come from more different worlds, or been more different in temperament. Jefferson, the optimist with enough faith in the innate goodness of his fellow man to be democracy’s champion, was an aristocratic Southern slaveowner, while Adams, the overachiever from New England’s rising middling classes, painfully aware he was no aristocrat, was a skeptic about popular rule and a defender of a more elitist view of government. They worked closely in the crucible of revolution, crafting the Declaration of Independence and leading, with Franklin, the diplomatic effort that brought France into the fight. But ultimately, their profound differences would lead to a fundamental crisis, in their friendship and in the nation writ large, as they became the figureheads of two entirely new forces, the first American political parties. It was a bitter breach, lasting through the presidential administrations of both men, and beyond. But late in life, something remarkable happened: these two men were nudged into reconciliation. What started as a grudging trickle of correspondence became a great flood, and a friendship was rekindled, over the course of hundreds of letters. In their final years they were the last surviving founding fathers and cherished their role in this mighty young republic as it approached the half century mark in 1826. At last, on the afternoon of July 4th, 50 years to the day after the signing of the Declaration, Adams let out a sigh and said, “At least Jefferson still lives.” He died soon thereafter. In fact, a few hours earlier on that same day, far to the south in his home in Monticello, Jefferson died as well. Arguably no relationship in this country’s history carries as much freight as that of John Adams of Massachusetts and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Gordon Wood has more than done justice to these entwined lives and their meaning; he has written a magnificent new addition to America’s collective story

From the great historian of the American Revolution, New York Times-bestselling and Pulitzer-winning Gordon Wood, comes a majestic dual biography of two of America’s most enduringly fascinating figures, whose partnership helped birth a nation, and whose subsequent falling out did much to fix its course.Thomas Jefferson and John Adams could scarcely have come from more different worlds, or been more different in temperament. Jefferson, the optimist with enough faith in the innate goodness of his fellow man to be democracy’s champion, was an aristocratic Southern slaveowner, while Adams, the overachiever from New England’s rising middling classes, painfully aware he was no aristocrat, was a skeptic about popular rule and a defender of a more elitist view of government. They worked closely in the crucible of revolution, crafting the Declaration of Independence and leading, with Franklin, the diplomatic effort that brought France into the fight. But ultimately, their profound differences would lead to a fundamental crisis, in their friendship and in the nation writ large, as they became the figureheads of two entirely new forces, the first American political parties. It was a bitter breach, lasting through the presidential administrations of both men, and beyond. But late in life, something remarkable happened: these two men were nudged into reconciliation. What started as a grudging trickle of correspondence became a great flood, and a friendship was rekindled, over the course of hundreds of letters. In their final years they were the last surviving founding fathers and cherished their role in this mighty young republic as it approached the half century mark in 1826. At last, on the afternoon of July 4th, 50 years to the day after the signing of the Declaration, Adams let out a sigh and said, “At least Jefferson still lives.” He died soon thereafter. In fact, a few hours earlier on that same day, far to the south in his home in Monticello, Jefferson died as well. Arguably no relationship in this country’s history carries as much freight as that of John Adams of Massachusetts and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Gordon Wood has more than done justice to these entwined lives and their meaning; he has written a magnificent new addition to America’s collective story

From a preeminent presidential historian comes a groundbreaking and often surprising saga of America’s wartime chief executives Ten years in the research and writing, Presidents of War is a fresh, magisterial, intimate look at a procession of American leaders as they took the nation into conflict and mobilized their country for victory. It brings us into the room as they make the most difficult decisions that face any President, at times sending hundreds of thousands of American men and women to their deaths. From James Madison and the War of 1812 to recent times, we see them struggling with Congress, the courts, the press, their own advisors and antiwar protesters; seeking comfort from their spouses, families and friends; and dropping to their knees in prayer. We come to understand how these Presidents were able to withstand the pressures of war–both physically and emotionally–or were broken by them. Beschloss’s interviews with surviving participants in the drama and his findings in original letters, diaries, once-classified national security documents, and other sources help him to tell this story in a way it has not been told before. Presidents of War combines the sense of being there with the overarching context of two centuries of American history. This important book shows how far we have traveled from the time of our Founders, who tried to constrain presidential power, to our modern day, when a single leader has the potential to launch nuclear weapons that can destroy much of the human race.

From a preeminent presidential historian comes a groundbreaking and often surprising saga of America’s wartime chief executives Ten years in the research and writing, Presidents of War is a fresh, magisterial, intimate look at a procession of American leaders as they took the nation into conflict and mobilized their country for victory. It brings us into the room as they make the most difficult decisions that face any President, at times sending hundreds of thousands of American men and women to their deaths. From James Madison and the War of 1812 to recent times, we see them struggling with Congress, the courts, the press, their own advisors and antiwar protesters; seeking comfort from their spouses, families and friends; and dropping to their knees in prayer. We come to understand how these Presidents were able to withstand the pressures of war–both physically and emotionally–or were broken by them. Beschloss’s interviews with surviving participants in the drama and his findings in original letters, diaries, once-classified national security documents, and other sources help him to tell this story in a way it has not been told before. Presidents of War combines the sense of being there with the overarching context of two centuries of American history. This important book shows how far we have traveled from the time of our Founders, who tried to constrain presidential power, to our modern day, when a single leader has the potential to launch nuclear weapons that can destroy much of the human race.

The author discussing the book. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6654z2KUt38

He was history’s most creative genius. What secrets can he teach us? The author of the acclaimed bestsellers Steve Jobs, Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin brings Leonardo da Vinci to life in this exciting new biography. Based on thousands of pages from Leonardo’s astonishing notebooks and new discoveries about his life and work, Walter Isaacson weaves a narrative that connects his art to his science. He shows how Leonardo’s genius was based on skills we can improve in ourselves, such as passionate curiosity, careful observation, and an imagination so playful that it flirted with fantasy. He produced the two most famous paintings in history, The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa. But in his own mind, he was just as much a man of science and technology. With a passion that sometimes became obsessive, he pursued innovative studies of anatomy, fossils, birds, the heart, flying machines, botany, geology, and weaponry. His ability to stand at the crossroads of the humanities and the sciences, made iconic by his drawing of Vitruvian Man, made him history’s most creative genius.

He was history’s most creative genius. What secrets can he teach us? The author of the acclaimed bestsellers Steve Jobs, Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin brings Leonardo da Vinci to life in this exciting new biography. Based on thousands of pages from Leonardo’s astonishing notebooks and new discoveries about his life and work, Walter Isaacson weaves a narrative that connects his art to his science. He shows how Leonardo’s genius was based on skills we can improve in ourselves, such as passionate curiosity, careful observation, and an imagination so playful that it flirted with fantasy. He produced the two most famous paintings in history, The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa. But in his own mind, he was just as much a man of science and technology. With a passion that sometimes became obsessive, he pursued innovative studies of anatomy, fossils, birds, the heart, flying machines, botany, geology, and weaponry. His ability to stand at the crossroads of the humanities and the sciences, made iconic by his drawing of Vitruvian Man, made him history’s most creative genius.

The journalist who broke the “Jihadi John” story draws on her personal experience to bridge the gap between the Muslim world and the West and explain the rise of Islamic radicalism Souad Mekhennet has lived her entire life between worlds. The daughter of a Turkish mother and a Moroccan father, she was born and educated in Germany and has worked for several American newspapers. Since the 9/11 attacks she has reported stories among the most dangerous members of her religion; when she is told to come alone to an interview, she never knows what awaits at her destination. In this compelling and evocative book, Mekhennet seeks to answer the question, “What is in the minds of these young jihadists, and how can we understand and defuse it?” She has unique and exclusive access into the world of jihad and sometimes her reporting has put her life in danger. We accompany her from Germany to the heart of the Muslim world — from the Middle East to North Africa, from Sunni Pakistan to Shia Iran, and the Turkish/ Syrian border region where ISIS is a daily presence. She then returns to Europe, first in London, where she uncovers the identity of the notorious ISIS executioner “Jihadi John,” and then in Paris and Brussels, where terror has come to the heart of Western civilization. Too often we find ourselves unable to see the human stories behind the headlines, and so Mekhennet – with a foot in many different camps – is the ideal guide to take us where no Western reporter can go. Her story is a journey that changes her life and will have a deep impact on us as well

The journalist who broke the “Jihadi John” story draws on her personal experience to bridge the gap between the Muslim world and the West and explain the rise of Islamic radicalism Souad Mekhennet has lived her entire life between worlds. The daughter of a Turkish mother and a Moroccan father, she was born and educated in Germany and has worked for several American newspapers. Since the 9/11 attacks she has reported stories among the most dangerous members of her religion; when she is told to come alone to an interview, she never knows what awaits at her destination. In this compelling and evocative book, Mekhennet seeks to answer the question, “What is in the minds of these young jihadists, and how can we understand and defuse it?” She has unique and exclusive access into the world of jihad and sometimes her reporting has put her life in danger. We accompany her from Germany to the heart of the Muslim world — from the Middle East to North Africa, from Sunni Pakistan to Shia Iran, and the Turkish/ Syrian border region where ISIS is a daily presence. She then returns to Europe, first in London, where she uncovers the identity of the notorious ISIS executioner “Jihadi John,” and then in Paris and Brussels, where terror has come to the heart of Western civilization. Too often we find ourselves unable to see the human stories behind the headlines, and so Mekhennet – with a foot in many different camps – is the ideal guide to take us where no Western reporter can go. Her story is a journey that changes her life and will have a deep impact on us as well

The full inside story of the breathtaking rise and shocking collapse of Theranos–the Enron of Silicon Valley–by the prize-winning journalist who first broke the story and pursued it to the end in the face of pressure and threats from the CEO and her lawyers. In 2014, Theranos founder and CEO Elizabeth Holmes was widely seen as the female Steve Jobs: a brilliant Stanford dropout whose startup “unicorn” promised to revolutionize the medical industry with a machine that would make blood tests significantly faster and easier. Backed by investors such as Larry Ellison and Tim Draper, Theranos sold shares in an early fundraising round that valued the company at $9 billion, putting Holmes’s worth at an estimated $4.7 billion. There was just one problem: the technology didn’t work. For years, Holmes had been misleading investors, FDA officials, and her own employees. When Carreyrou, working at the Wall Street Journal, got a tip from a former Theranos employee and started asking questions, both Carreyrou and the Journal were threatened with lawsuits. Undaunted, the newspaper ran the first of dozens of Theranos articles in late 2015. By early 2017, the company’s value was zero and Holmes faced potential legal action from the government and her investors. Here is the riveting story of the biggest corporate fraud since Enron, a disturbing cautionary tale set amid the bold promises and gold-rush frenzy of Silicon Valley

The full inside story of the breathtaking rise and shocking collapse of Theranos–the Enron of Silicon Valley–by the prize-winning journalist who first broke the story and pursued it to the end in the face of pressure and threats from the CEO and her lawyers. In 2014, Theranos founder and CEO Elizabeth Holmes was widely seen as the female Steve Jobs: a brilliant Stanford dropout whose startup “unicorn” promised to revolutionize the medical industry with a machine that would make blood tests significantly faster and easier. Backed by investors such as Larry Ellison and Tim Draper, Theranos sold shares in an early fundraising round that valued the company at $9 billion, putting Holmes’s worth at an estimated $4.7 billion. There was just one problem: the technology didn’t work. For years, Holmes had been misleading investors, FDA officials, and her own employees. When Carreyrou, working at the Wall Street Journal, got a tip from a former Theranos employee and started asking questions, both Carreyrou and the Journal were threatened with lawsuits. Undaunted, the newspaper ran the first of dozens of Theranos articles in late 2015. By early 2017, the company’s value was zero and Holmes faced potential legal action from the government and her investors. Here is the riveting story of the biggest corporate fraud since Enron, a disturbing cautionary tale set amid the bold promises and gold-rush frenzy of Silicon Valley

Oleg Gordievsky was a spy like no other. The product of a KGB family and the best Soviet institutions, the savvy Russian eventually saw the lies and terrors of the regime for what they were, a realization that turned him irretrievably toward the West. His career eventually brought him to the highest post in the KGB’s London station-but throughout that time he was secretly working for MI6, the British intelligence service”-

Oleg Gordievsky was a spy like no other. The product of a KGB family and the best Soviet institutions, the savvy Russian eventually saw the lies and terrors of the regime for what they were, a realization that turned him irretrievably toward the West. His career eventually brought him to the highest post in the KGB’s London station-but throughout that time he was secretly working for MI6, the British intelligence service”-

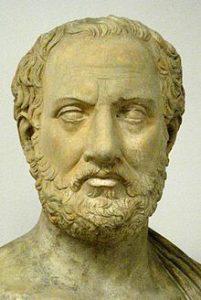

CHINA AND THE UNITED STATES ARE HEADING TOWARD A WAR NEITHER WANTS. The reason is Thucydides’s Trap, a deadly pattern of structural stress that results when a rising power challenges a ruling one. This phenomenon is as old as history itself. About the Peloponnesian War that devastated ancient Greece, the historian Thucydides explained: “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” Over the past 500 years, these conditions have occurred sixteen times. War broke out in twelve of them. Today, as an unstoppable China approaches an immovable America and both Xi Jinping and Donald Trump promise to make their countries “great again,” the seventeenth case looks grim. Unless China is willing to scale back its ambitions or Washington can accept becoming number two in the Pacific, a trade conflict, cyberattack, or accident at sea could soon escalate into all-out war. In Destined for War, the eminent Harvard scholar Graham Allison explains why Thucydides’s Trap is the best lens for understanding U.S.-China relations in the twenty-first century. Through uncanny historical parallels and war scenarios, he shows how close we are to the unthinkable. Yet, stressing that war is not inevitable, Allison also reveals how clashing powers have kept the peace in the past — and what painful steps the United States and China must take to avoid disaster today.

CHINA AND THE UNITED STATES ARE HEADING TOWARD A WAR NEITHER WANTS. The reason is Thucydides’s Trap, a deadly pattern of structural stress that results when a rising power challenges a ruling one. This phenomenon is as old as history itself. About the Peloponnesian War that devastated ancient Greece, the historian Thucydides explained: “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” Over the past 500 years, these conditions have occurred sixteen times. War broke out in twelve of them. Today, as an unstoppable China approaches an immovable America and both Xi Jinping and Donald Trump promise to make their countries “great again,” the seventeenth case looks grim. Unless China is willing to scale back its ambitions or Washington can accept becoming number two in the Pacific, a trade conflict, cyberattack, or accident at sea could soon escalate into all-out war. In Destined for War, the eminent Harvard scholar Graham Allison explains why Thucydides’s Trap is the best lens for understanding U.S.-China relations in the twenty-first century. Through uncanny historical parallels and war scenarios, he shows how close we are to the unthinkable. Yet, stressing that war is not inevitable, Allison also reveals how clashing powers have kept the peace in the past — and what painful steps the United States and China must take to avoid disaster today.

See entry about Thucydides Thucydides

See entry about Thucydides Thucydides

Two pieces shared by Tom Igoe

Graham-Allison-Opinion-in-Weekend-Financial-Times

The-Crisis-in-U.S.-China-Relations-WSJ.pdf

The Truth About the Liberal Order

Dynamic growth of China’s GDP.