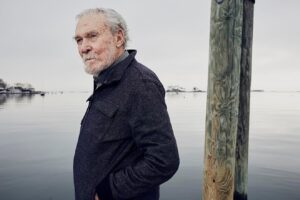

Bruce Kirby, a Canadian-born journalist, Olympic sailor and self-taught naval architect whose design for a lightweight fiberglass dinghy, originally sketched on a piece of yellow legal paper, changed the face of sailing, died on Monday at his home in the village of Rowayton in Norwalk, Conn. He was 92.

Bruce Kirby, a Canadian-born journalist, Olympic sailor and self-taught naval architect whose design for a lightweight fiberglass dinghy, originally sketched on a piece of yellow legal paper, changed the face of sailing, died on Monday at his home in the village of Rowayton in Norwalk, Conn. He was 92.

His wife, Margo Kirby, confirmed his death.

Dinghy racing in North America and Europe in the late 1960s revolved around the International 14, a lightweight, 14-foot, two-person craft, and by then Mr. Kirby had carved out a niche for himself moonlighting as a designer in the 14 sailing class, spinning off variations on the original design that would have the dinghy planing and skipping across the water’s surface. His day job was as editor of the sailing magazine One-Design & Offshore Yachtsman in Chicago.

He had also won renown racing 14s and was a three-time Olympian for Canada, though without winning a medal.

One day in 1969 he received a phone call from a friend, Ian Bruce, an industrial designer and boating enthusiast in Montreal who as a side job had been building complex wooden hulls to Mr. Kirby’s I-14 designs and selling them. But with little margin in that business, he was looking for a new small-boat design — an easy-to-build, fiberglass sailboat that a solo sailor could race and that would help keep his I-14 business rolling.

Grabbing a yellow legal pad, Mr. Kirby promptly drew one up, envisioning a lightweight fiberglass hull, just under 14 feet long. It would eventually be christened the Laser and become a worldwide phenomenon.

“When Ian called him in 1969, Bruce was doodling,” said Peter Bjorn, a former partner in Performance Sailcraft, the first manufacturer of the Laser. “Ian lofted it,” he added, referring to the drawing of final plans, “in the fall of 1970, and they tweaked it. There was snow on the ground when they finally put the molds together. Bruce came and sailed it. And that was it.”

The boat was rigged up for the 1971 New York Boat Show with a sticker price of $595 (about $3,780 today). Before the doors closed, 144 were sold.

“All of a sudden,” Mr. Bjorn said, “there was something that wasn’t quite a toy — they took a bit to sail — and you could take money straight out of your pocket to buy it and throw it on the roof of your car.”

Coming in colors like orange, yellow, light blue and British racing green, the boat was an instant sensation. Its streamlined simplicity — with a teak tiller and a sail whose sleeve slid over an aluminum mast — made the Laser as basic in design as the Windsurfer and the Hobie Cat catamaran, both of which had arrived on the beach boat scene around the same time. What made the Laser different from them, however, was that it could be ideal both for cruising around with friends and for performance racing by a single sailor.

“It was a boat you could control with your body,” said Peter Commette, winner of the first Laser world championships, in 1974.

More than 250,000 of the boats have been built worldwide since 1970, making Mr. Kirby’s creation one of the most influential sailboat designs of all time. The Laser, now called the ILCA, for the International Laser Class Association, is used for men’s and women’s single-handed events in the Olympics.

Mr. Kirby came to call his original legal pad drawing the “million dollar doodle.” The royalties he received allowed him to leave his day job, launching him into an eclectic boat-design career that touched every corner of the sport, from the America’s Cup to junior sailing to cruising craft for shallow estuaries, and established him as one of the world’s pre-eminent boat designers.

He followed in his father’s wake, racing small boats on the Ottawa River during Canada’s fleeting summers and devouring copies of Yachting magazine in the winter. The best small-boat sailors of the time raced International 14s, two-person boats, each usually built in the home or garage according to design specifications. Mr. Kirby began to travel and rake in trophies in the class.

If his first love was sailing, his second was journalism. A lung ailment kept him out of college, and through his father’s connections he became, at 20, a reporter for The Ottawa Journal for $25 a week (the equivalent of about $290 in Canadian money today).

His knowledge of sailing brought him reporting stints from an ocean sailing yacht in Europe. Moving to The Montreal Star, he joined its copy desk but also covered the America’s Cup. He headed for Chicago to become editor of One-Design & Offshore Yachtsman in 1965.

Never far from sailing, Mr. Kirby qualified for the 1956 Olympics, in Melbourne, Australia, in the single-handed Finn class. He went on to sail in the 1964 Games (in Tokyo) in the same class and in the 1968 games (centered in Mexico City) in the two-person Star class.

He worked out his designs using intuition and from reading Norman Skene’s “Elements of Yacht Design.” His I-14 designs were steppingstones to the Laser, which in turn opened doors, bringing him a host of design commissions, including one for a yacht named Runaway, Canada’s 1981 entry in the Admiral’s Cup international competition. Runaway put him on a global stage.

Then came Canada I, the 1983 Canadian entry for the America’s Cup, and its design lifted Kirby’s reputation to new heights.

Though Canada I made the semifinals, the Canadians were no match for the Australians, who went on to break the longest winning streak in sports history — 132 years — by defeating the Americans that year for the cup.

Kirby designed another Cup boat, the Canada II, for the 1987 series. He also produced a total of 63 innovative and popular sailboat designs, including the 23-foot Sonar keelboat, which he created for the Noroton Yacht Club in Darien, Conn., where he was a commodore. The Sonar has been sailed on every continent and is used in the Paralympic Games.

His Laser was selected for the men’s single-handed sailing event for the 1996 Olympics and for the women’s single-handed event in 2008.

“For me the big thing I love about the Laser is the simplicity of design,” Sarah Douglas, a Canadian representative in this year’s Tokyo Olympics, said in a phone interview from Japan. “I grew up in Barbados. It’s the most accessible boat. If the Laser wasn’t in the Games, I don’t know how smaller nations can compete in sailing.”

Kirby, who became a naturalized American citizen, lived along the Five Mile River in Rowayton for 45 years, designing in his basement. He and Mr. Bruce were awarded the Order of Canada for their contributions to sailing, and Mr. Kirby was inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame in 2012.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by two daughters, Kelly Kirby and Janice Duffy, and two granddaughters.

“Physically he was quite compromised,” Margo Kirby, his wife, said. “He blamed it on hiking for years on small boats. He said he’d do it all over again.”